It's 2:23am and the rain's just started

You can hear the sleeping breath of your children and the grunting sighs of the dog

You can feel the prickling buzz of fatigue down your left leg but the moment is wrong

(If sleep is a wave, as your therapist used to say, the tide is receding away past the horizon)

Googling, not surprisingly, doesn't help.

So what is there to do but try to unhook:

let the mind meander:

- the taste of Pad Thai at dinner

- the disquisition on the growing of orchids by the lady in the supermarket

- the discovery of exoplanets and the hope of other (or, perhaps, just some) intelligence

- the play of half-sick shadows on the wall

One of the children's picture books is about a soft toy elephant called Harry

who is unable to sleep

And you think about that, and think, like Harry:

what if sleep never ever comes at all?

It doesn't matter. Here in the deep marches

where weird things climb out from inside

it's not relevant what the clock says

It only matters what battles you can fight

and which ones you can walk away from

- Kathy, 24/02/17

Friday, February 24, 2017

Monday, February 20, 2017

Working in the 80s

Today has been 80s working music day.

I have pumped out a metric tonne of work to the dulcet sounds of:

80s cheese is total rocket fuel for writing, it seems! :-D

While many of these are total bangers, I feel like nothing screams EIGHTIES quite like this one. Enjoy. You're welcome.

I have pumped out a metric tonne of work to the dulcet sounds of:

- Madonna

- Cyndi Lauper

- Aha

- Starship

- Michael Jackson

- Duran Duran

- Wham!

- Guns n Roses

- The Bangles

- Fleetwood Mac

- Tears for Fears

- Bonnie Tyler

- Petshop Boys

- A bunch of others!

80s cheese is total rocket fuel for writing, it seems! :-D

While many of these are total bangers, I feel like nothing screams EIGHTIES quite like this one. Enjoy. You're welcome.

Wednesday, February 15, 2017

Late summer (Poem)

walking home from school, a Siamese cat stares at us

eyes as blue as litmus paper bathed in alkaline

why does the earth stay in place? she says, and

why don't my friends like each other?

the sky is equivocating again, and the negative moon

hangs as pale as leftover porridge in the left quarter

all the neighbours' roses are shrivelled and gone,

just dusty brown fragments, and a few rosehips

it's so hot! she says, and I say, it really is,

let's get home and have a drink

the pavement heats the soles of our shoes,

and the flies won't leave us alone

why is it so hot? she asks, and I don't know what to tell her -

because it's summer, obviously, but maybe, too,

because the poor dear world is now a stew cauldron

and every year the flame climbs a little more

and every year's the hottest, and every measure

speaks in tongues of waste to come

but this is my child, so I don't say that;

I say, because it's still the summer!

and she takes my hand, warm and damp in hers,

and we find our front door.

- Kathy, 15/02/17

eyes as blue as litmus paper bathed in alkaline

why does the earth stay in place? she says, and

why don't my friends like each other?

the sky is equivocating again, and the negative moon

hangs as pale as leftover porridge in the left quarter

all the neighbours' roses are shrivelled and gone,

just dusty brown fragments, and a few rosehips

it's so hot! she says, and I say, it really is,

let's get home and have a drink

the pavement heats the soles of our shoes,

and the flies won't leave us alone

why is it so hot? she asks, and I don't know what to tell her -

because it's summer, obviously, but maybe, too,

because the poor dear world is now a stew cauldron

and every year the flame climbs a little more

and every year's the hottest, and every measure

speaks in tongues of waste to come

but this is my child, so I don't say that;

I say, because it's still the summer!

and she takes my hand, warm and damp in hers,

and we find our front door.

- Kathy, 15/02/17

Wednesday, February 8, 2017

Naming the thing

The other day, I was discussing work with a friend I haven't seen for a while.

"So you don't work for the university anymore?" she said.

"Well..." I said. "I sort of do, but I'm not employed there though. They're one of my big clients."

She looked a bit confused. "So you're a - what?"

I hemmed and hawed and finally came down on the side of telling her that I was a consultant, which felt really pretentious to be honest, but I realised later probably didn't answer her real question, which was: how do I get paid?

(Insert freelancer joke here along the lines of "infrequently and with difficulty lol")

It strikes me that many, if not most, employees have a bit of muddly thinking going on when it comes to the 30% of us who work but aren't on some organisation's payroll. We of the Quarterly Tax Nightmare, let's say. I have had great difficulty explaining what it is I do, and how I do it, to other people at times.

I have finally come up with this taxonomy that I think works. It goes like this:

Do I get paid a wage or salary, and does someone else deal with the tax office and pay super on my behalf?

YES - Employee

NO - Not employee but could be a few other things

Do I get paid for my work on invoices issued to clients or customers, and do I have more than one client or customer?

YES - Independent contractor OR contract business OR freelancer

NO - If I issue invoices but have only one client - Subcontractor

Do I employ other people?

YES - Business

NO - Might still be a small business, but see below

Do I sell stuff (eg goods) rather than just my labour?

YES - Small business

NO - Might still be a small business, but see below

Do I have an ACN as well as an ABN, and / or do I regularly use subcontracted labour?

YES - Small business operator

NO - Sole Trader

Do I have increasing anxiety as each quarter ends, culminating in a mini meltdown when the bloody BAS is due again?

YES - Oh yeah, you're a freelancer / sole trader / small business operator

NO - Lucky old (employed) you!

So my answer to my friend should probably have been that I am a Policy Consultant (that's my job title) operating as a sole trader but moving towards being a small business (that's my mode of getting paid). I use subcontractors a little and it will probably grow this year, so I am in a transitional phase, I guess.

I'm also a person who works at home for about 70% of the time I bill, which brings me into the ambit of a whole 'nuther array of memes and conventions - working from home is not the same as working in an office (I personally find it blissful, but it sure isn't for everyone). It involves a rethinking of yoir approach to time management and organisation that can be tragically ill-advised for many, at least at first, but there is no denying the benefits if you get it right.

So then: I'm a WAH Policy Consultant, Sole Trader, reasonable rates, by request, at your service :-P

"So you don't work for the university anymore?" she said.

"Well..." I said. "I sort of do, but I'm not employed there though. They're one of my big clients."

She looked a bit confused. "So you're a - what?"

I hemmed and hawed and finally came down on the side of telling her that I was a consultant, which felt really pretentious to be honest, but I realised later probably didn't answer her real question, which was: how do I get paid?

(Insert freelancer joke here along the lines of "infrequently and with difficulty lol")

It strikes me that many, if not most, employees have a bit of muddly thinking going on when it comes to the 30% of us who work but aren't on some organisation's payroll. We of the Quarterly Tax Nightmare, let's say. I have had great difficulty explaining what it is I do, and how I do it, to other people at times.

I have finally come up with this taxonomy that I think works. It goes like this:

Do I get paid a wage or salary, and does someone else deal with the tax office and pay super on my behalf?

YES - Employee

NO - Not employee but could be a few other things

Do I get paid for my work on invoices issued to clients or customers, and do I have more than one client or customer?

YES - Independent contractor OR contract business OR freelancer

NO - If I issue invoices but have only one client - Subcontractor

Do I employ other people?

YES - Business

NO - Might still be a small business, but see below

Do I sell stuff (eg goods) rather than just my labour?

YES - Small business

NO - Might still be a small business, but see below

Do I have an ACN as well as an ABN, and / or do I regularly use subcontracted labour?

YES - Small business operator

NO - Sole Trader

Do I have increasing anxiety as each quarter ends, culminating in a mini meltdown when the bloody BAS is due again?

YES - Oh yeah, you're a freelancer / sole trader / small business operator

NO - Lucky old (employed) you!

So my answer to my friend should probably have been that I am a Policy Consultant (that's my job title) operating as a sole trader but moving towards being a small business (that's my mode of getting paid). I use subcontractors a little and it will probably grow this year, so I am in a transitional phase, I guess.

I'm also a person who works at home for about 70% of the time I bill, which brings me into the ambit of a whole 'nuther array of memes and conventions - working from home is not the same as working in an office (I personally find it blissful, but it sure isn't for everyone). It involves a rethinking of yoir approach to time management and organisation that can be tragically ill-advised for many, at least at first, but there is no denying the benefits if you get it right.

So then: I'm a WAH Policy Consultant, Sole Trader, reasonable rates, by request, at your service :-P

Monday, February 6, 2017

Riding the Light (Story)

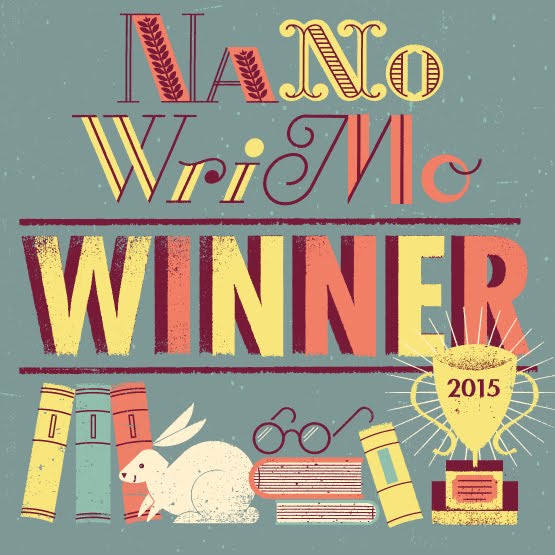

This is the third, and for now, final, short story in the world / content that supports my novel in progress (the novel is called The True Size of the Universe). Writing these three stories has really helped me reconnect with the worldview of the novel, and I feel ready to jump back into it now, so I'll be concentrating on that in whatever time I can salvage for writing.

In terms of timeline, I have now written or part-written five things within this universe / master story; they go like this:

In terms of timeline, I have now written or part-written five things within this universe / master story; they go like this:

- Theory of Mind (Verse novella, unpublished, completed in NaNoWriMo 2015) - Set on Earth, approx 80 years from present

- The Desolation of Vesta (Short story, published to blog) - Set on the planetoid Vesta, approx 200 years from present

- Riding the Light (Short story, published to blog) - Set in the asteroid Belt, approx 250 years from present

- The Gardens of Demos Attina (Short story, published to blog) - Set on the moon world of Demos, approx 280 years from present

- The True Size of the Universe (Novel, in progress) - Set in deep space, approx 400 years from present

As Shakespeare says, the past is prologue. Getting a deeper feel for where my novel comes from has helped me see what's wrong with it in its current form and understand why I've been blocked in moving it forward. Hopefully now I can get moving again on both writing and rewriting.

This story does connect up to the novel, as it's the tale of how the grandfather of my main protagonist in the novel, Ciro Grady, lost an eye when mining in the Belt. His name is Jock, and while this isn't primarily his story, he's important in it.

This story does connect up to the novel, as it's the tale of how the grandfather of my main protagonist in the novel, Ciro Grady, lost an eye when mining in the Belt. His name is Jock, and while this isn't primarily his story, he's important in it.

Riding the Light

Things can get pretty damn dull, out in the Belt.

Oh, we work hard and long, when we're working a seam. The shipbots do most of the suction, of course, but grading and separating and plotting the path for the little mech critters to follow - that's a human job, and one that calls for instinct and experience and a lot of time squinting at fragments so small you'd swear they were hardly there.

But between the seams, in the long, spacey weeks of cruising, waiting for a sniff of something good ... well, day-cycles can go on forever, and the boredom of it can make people a little off, to put it mildly. That doesn't work out so well when you need people to swing into action at a moment's notice. Holding yourself ready even when nothing whatever is happening is a skill, and it takes time to learn it.

Seasoned crews do better, of course, and ones that are well-matched, used to each other, do best of all. Any Belt Captain's worst nightmare is taking out a rookie crew, but the Guild makes us take out newbs, at least sometimes.

Oh, the logic's sound enough. How else will any new workers come through unless someone takes the time and trouble to blood them? That doesn't mean anyone wants to be Johnny-on-the-spot, though.

You can usually tell who's in the frame for a rookie run by the volume of the groans in port on Demos or Mars Prima, the big assignment stations Earthside of the Belt. I hear Callisto Augusta is sending newbs out too, squeezing mineships from both ends these days. Situation normal for the Guild of Moons, but not fantastic for Captains trying to make their pile before the Belt makes them dead.

I had groaned, loud enough to be heard in Copernica Luna, the last time we docked at Mars Prima.

----------------------------------------------------

"Captain T'vela, sir -"

"Cadet Geryon."

He stood, flushed with exertion, in the narrow gangway leading to the cargo hold. I sighed internally. Shuffling a few dozen mixed-ore crates, with the aid of the bots, shouldn't have raised a sweat in anyone, but this kid was neither land nor space fit - he'd be better in a Guild office somewhere in a City dome, approving permits and soothing down outraged passengers when the ships, as ships inevitably did, ran late or altered course without warning.

"Captain ... First Officer Grady. He says there's something you should see."

I raised my eyebrow slightly, but followed him as he led the way back down the dim corridor to the cargo.

Jock was standing in the middle of the half-empty hold, his hand on the control of one of the little cleaner-bots we'd specced up to when we were in Prima. His gaze was distant and he seemed lost in thought - not a particularly common state for him. The best second a Captain could want, and a longtime friend, but not a deep thinker, Jock.

"Jock?" I said, moving to his side. "Mikel here says you found something?"

He turned to face me, and I saw for the first time the depth of his bewilderment. "Aye, Christina," he said. "Well, perhaps. I don't know. I can't - I don't know."

"Explain?"

Jock handed me an assay tablet, his thick forefinger jabbing at the third line. "There!"

I looked at the tablet, then stared again in confusion. "That can't be right."

Jock snorted. "You're telling me! It can't be, but if it is ..."

"What in space could possibly -"

"It might be an instrument failure. Although I sent five bots."

I tipped my head, trying to dislodge the dread building up in my neck. Jock was right; this was serious. It could be fatal to us all.

First things first. "Are we going to need anyone else?"

Jock thought for a minute, then said, "Alexis, definitely. Roy, maybe? I think we're going to have to go EVA for this. To work it out."

"EVA? What for? The bots can -"

Jock's head went back. "No. I already sent five of them, remember, and what they're reporting - it doesn't make any sense. We're going to have to go look. Great gods, Christina! Don't you think I know my job by now?"

Ignoring Mikel Geryon's bug-eyes (we tend to cut good miners a lot of slack, out in the black wilds), I said, "EVA's a big risk, out here. With Vesta decommissioned, we're a good 10 days' sailing from the nearest port, and even that's a midget facility on Hera 7. Very basic field hospital conditions only, they can't treat for -"

"Any serious loss. I know, Captain." Jock ran his hands through his thick black hair. "But if we don't go, none of us may make it back anyway. We've got to know."

The gasping behind me was pronounced enough to agitate the cleaner-bot in Jock's hand; it twitched to get away, desperate to investigate. They were useful enough, but I'd already had opportunity to wish they'd been programmed with less overwhelming compulsion to respond to noise in case it signalled a mess.

Without turning my head, I said, "Cadets Tang and Desmullah. Do you know where Harris and Patel are? We may have a need for them shortly."

Anise Tang, a round little girl with cherry-blossom-pink eyes, fluted "They are on sleep rotation, Captain. Shall I rouse them?" For all her cotton-candy eyes and engineered child soprano, she was the toughest and most pragmatic of the three. Which was not saying much; but I'll grant that she seemed less spooked than Geryon, who had sunk onto a crate and was hyperventilating, or Quinn Desmullah, who looked like he was about to lose his lunch.

"Not the best bloody time to be running on half-rations," Jock grunted, but softly. He hadn't been happy about having to leave two of our crew in port to board the three newbs, but he was fair-minded enough not to take it out of their hides. Mostly.

I nodded to Tang. "Yes, rouse them. We'll need to convene a ship meeting right away."

-------------------------------------------------------------

Three scraps of humanity, hanging in the void, separated from infinity by a quad layer of insulation suit and a moulded rebreather. Three blind mice, probing the space dust, tethers holding us to the ship as we spin slowly, slowly, in this glowing night. Three Belt miners -

Or, no. Two, and what I am beginning to fear is a mistake.

Jock had laid out the problem and the task in his customary unadorned fashion, as Roy Harris and Alexis Patel rubbed sleep from their eyes and struggled into their boots.

"Three, to go?" Alexis had said, already turning towards the rebreather rack. "I'll suit up, Captain. Do you want Roy, or will Jock -"

"Roy should stay. We will need his skills to draw us home." Harris inclined his head towards me, his deep calm soothing.

Alexis was already halfway into her suit when Anise Tang spoke, softly but clearly. "Captain."

I paused. "Cadet?"

"Captain, I believe the Guild requirements specify that cadets must be given opportunity to participate in EVA, should the ship have occasion to engage in one. During the course of its journey."

Roy sighed, while Alexis opened her mouth to speak, but Jock got there first. "Are you touched, little girl?" he barked disbelievingly. "Did you hear what I said? What the Captain said? This is no ship-shining securewalk we're talking about here. This is a job for grown-ups -"

"I heard." Tang's voice was like a starling's song laced with steel - a peculiar, unsettling effect. "We all signed danger disclaimers to board this vessel, First Officer. We will not learn enough without taking some risks. We are prepared." I stole a glance at Geryon and Desmullah, skulking behind her. They didn't look particularly prepared; they looked, in fact, as scared as we should all be, given the circumstances.

I said, "Alright, Tang. Point made." Jock began to protest, but I cut him off with my hand. "However. It is my judgement as Captain that taking all three of you would pose an unacceptable risk to the mission, and the ship." Tang's brow creasd slightly, as I went on, "One of you may take the place of Officer Patel. Only one."

So now here we are, circling in these fireflies made of the dust of stars - Jock, me, and Anise Tang. Untried, untested, and already unravelling as we move away from sanctuary in the black wilds of the Belt.

---------------------------------------------------------------------

The head mikes are scratchy. "Christina - spin left," says Jock tersely, his voice granulated by the transmission.

"Captain, Captain, I see something -"

"Where are you, Tang?" I swivel in frustration, but she's moved out of my sightlines and that's not good. Visual at all times is the rule, but she's unblooded and the rules aren't in her veins yet.

"Captain, I don't know what it is, I don't know -"

Jock interjects. "It's alright, lass," he says, his voice low, gentling her. Now that it's done and we're here with her, he knows what must be. "Tell us what you see, we'll find you."

Her breathing's ragged in the headpiece, but she says, "Tiny stars. I see ... tiny stars. Here, in front of me."

There is a pause as long as twenty heartbeats.

"Anise," I say, barely daring to breathe, "can you pull back on your tether? Can you draw back towards the ship? If you can do that, do it, and don't touch anything, alright? Just don't -"

That is when she starts screaming.

Jock's swearing in my ear and I am spinning, spinning, eyes going left right left up down right where is she where where

Then I see her, and I know it's almost certainly already too late. She's lit up like a candle on a Yule tree, her body rigid, her mouth open inside her helmet as a continuous stream of astounded agony pours out of her.

Jock is yelling at me now, Get back, get back, great gods Christina she's gonna blow any minute and I look back towards my ship, just a speck in the distance now, the dull coppery sheen of its hull a lodestone, and I say:

"Anise, Anise, I'm coming."

Jock's swearing at me in five languages now, including one I've sure has been dead since Earth fell, but I stay my course, spinning through the emptiness towards the sickly shimmering, towards the cadet, towards tiny speckled fragments of hell.

"Anise. Listen to me."

Her screams have subsided into sobs now, but they slacken, fall silent. I press my advantaage.

"You've been pierced by Casey subatoms. Do you know what they are?"

She sobs a hiccup. "Old star radiants. Rogue clusters of them out past Saturn -"

"And, apparently, in the Belt," I finish. "Although no one knew so, until now." Jock's jabbering away to Alexis back on board ship, but I mute him, moving slowly towards the shining girl.

"Yes. That's what's happened. We need to get you back to the ship and into a containment pod as soon as we can do that."

Silence. Then: "It hurts, Captain."

Her voice is fading, and I know the likelihood is she's already dead, but still I spin, concentric circles moving closer to my target with each minute.

When I get close enough to see her face through the visor, I see that her eyes, once the prettiest floss pink the geneticists of Luna could summon, are now crimson red, sightless, with blood trickling from the tear ducts like the sorrow of an ancient star.

"Anise," I say, and she raises her head towards me.

"I wanted -" she says. "My parents, they wanted me to go for a Guild marriage, be safe. But I wanted ..." Her voice is weak, distant, and hands are lax beside her.

"Come on, child," I say, as I snap her tether string to my waist belt. "Let's get you home, then." I unmute my second mike. "Jock?"

"Christina, where -"

"Jock, I'm bringing her in. Get Alexis to have the radipod ready, yes? We're coming in from the upper left."

He says nothing for a moment, then: "Christina. Any minute, she could -"

"I'll be coming in hard," I say. "Be ready, alright?"

Spinning through the dark, spinning silently, two locked-together specks of flesh, one aglow, one in shadow. People are weightless in space, but I feel the weight of her in my arms, nonetheless. She's completely quiet now; only her life signs monitor tells me she's still breathing.

"Captain!" Alexis's voice is loud, anxious, in my ear. "I've prepped the radipod, but -"

"Good. Thank you, Alexis." I can hear the downward fade in my own voice, and I look down at my hand, now starting to glow in the blackness. It was inevitable, I suppose.

"Captain, we wonder if - If she caught a full load, well -"

"We'll head straight for the field hospital. Tell Roy, yes?" And now my voice is crackling like space static even though I'm within clear visual of the ship now, in the cleanest of comm ranges.

Jock cuts in. "I'm back in the bay, Captain. Ready to catch you, when you get here."

"Thank you," I say, and then I say no more. It feels like there is no breath to speak and the pain in my chest is growing.

Thirty seconds later, I hear my own breath inside my head and I know.

The ship looms hugely in my misted sightline and I unclip Anise from my belt. "Live, then," I say, and push her towards Jock's waiting arms. They're all clustered at the dock, even the cadets, and they're shouting something towards me bur it doesn't make any sense anymore and I push away, frog-legs pressed against the hull for traction, aiming to go deep, deep, deep, before -

All the tiny stars recombine, and make an infant sun.

Oh, we work hard and long, when we're working a seam. The shipbots do most of the suction, of course, but grading and separating and plotting the path for the little mech critters to follow - that's a human job, and one that calls for instinct and experience and a lot of time squinting at fragments so small you'd swear they were hardly there.

But between the seams, in the long, spacey weeks of cruising, waiting for a sniff of something good ... well, day-cycles can go on forever, and the boredom of it can make people a little off, to put it mildly. That doesn't work out so well when you need people to swing into action at a moment's notice. Holding yourself ready even when nothing whatever is happening is a skill, and it takes time to learn it.

Seasoned crews do better, of course, and ones that are well-matched, used to each other, do best of all. Any Belt Captain's worst nightmare is taking out a rookie crew, but the Guild makes us take out newbs, at least sometimes.

Oh, the logic's sound enough. How else will any new workers come through unless someone takes the time and trouble to blood them? That doesn't mean anyone wants to be Johnny-on-the-spot, though.

You can usually tell who's in the frame for a rookie run by the volume of the groans in port on Demos or Mars Prima, the big assignment stations Earthside of the Belt. I hear Callisto Augusta is sending newbs out too, squeezing mineships from both ends these days. Situation normal for the Guild of Moons, but not fantastic for Captains trying to make their pile before the Belt makes them dead.

I had groaned, loud enough to be heard in Copernica Luna, the last time we docked at Mars Prima.

----------------------------------------------------

"Captain T'vela, sir -"

"Cadet Geryon."

He stood, flushed with exertion, in the narrow gangway leading to the cargo hold. I sighed internally. Shuffling a few dozen mixed-ore crates, with the aid of the bots, shouldn't have raised a sweat in anyone, but this kid was neither land nor space fit - he'd be better in a Guild office somewhere in a City dome, approving permits and soothing down outraged passengers when the ships, as ships inevitably did, ran late or altered course without warning.

"Captain ... First Officer Grady. He says there's something you should see."

I raised my eyebrow slightly, but followed him as he led the way back down the dim corridor to the cargo.

Jock was standing in the middle of the half-empty hold, his hand on the control of one of the little cleaner-bots we'd specced up to when we were in Prima. His gaze was distant and he seemed lost in thought - not a particularly common state for him. The best second a Captain could want, and a longtime friend, but not a deep thinker, Jock.

"Jock?" I said, moving to his side. "Mikel here says you found something?"

He turned to face me, and I saw for the first time the depth of his bewilderment. "Aye, Christina," he said. "Well, perhaps. I don't know. I can't - I don't know."

"Explain?"

Jock handed me an assay tablet, his thick forefinger jabbing at the third line. "There!"

I looked at the tablet, then stared again in confusion. "That can't be right."

Jock snorted. "You're telling me! It can't be, but if it is ..."

"What in space could possibly -"

"It might be an instrument failure. Although I sent five bots."

I tipped my head, trying to dislodge the dread building up in my neck. Jock was right; this was serious. It could be fatal to us all.

First things first. "Are we going to need anyone else?"

Jock thought for a minute, then said, "Alexis, definitely. Roy, maybe? I think we're going to have to go EVA for this. To work it out."

"EVA? What for? The bots can -"

Jock's head went back. "No. I already sent five of them, remember, and what they're reporting - it doesn't make any sense. We're going to have to go look. Great gods, Christina! Don't you think I know my job by now?"

Ignoring Mikel Geryon's bug-eyes (we tend to cut good miners a lot of slack, out in the black wilds), I said, "EVA's a big risk, out here. With Vesta decommissioned, we're a good 10 days' sailing from the nearest port, and even that's a midget facility on Hera 7. Very basic field hospital conditions only, they can't treat for -"

"Any serious loss. I know, Captain." Jock ran his hands through his thick black hair. "But if we don't go, none of us may make it back anyway. We've got to know."

The gasping behind me was pronounced enough to agitate the cleaner-bot in Jock's hand; it twitched to get away, desperate to investigate. They were useful enough, but I'd already had opportunity to wish they'd been programmed with less overwhelming compulsion to respond to noise in case it signalled a mess.

Without turning my head, I said, "Cadets Tang and Desmullah. Do you know where Harris and Patel are? We may have a need for them shortly."

Anise Tang, a round little girl with cherry-blossom-pink eyes, fluted "They are on sleep rotation, Captain. Shall I rouse them?" For all her cotton-candy eyes and engineered child soprano, she was the toughest and most pragmatic of the three. Which was not saying much; but I'll grant that she seemed less spooked than Geryon, who had sunk onto a crate and was hyperventilating, or Quinn Desmullah, who looked like he was about to lose his lunch.

"Not the best bloody time to be running on half-rations," Jock grunted, but softly. He hadn't been happy about having to leave two of our crew in port to board the three newbs, but he was fair-minded enough not to take it out of their hides. Mostly.

I nodded to Tang. "Yes, rouse them. We'll need to convene a ship meeting right away."

-------------------------------------------------------------

Three scraps of humanity, hanging in the void, separated from infinity by a quad layer of insulation suit and a moulded rebreather. Three blind mice, probing the space dust, tethers holding us to the ship as we spin slowly, slowly, in this glowing night. Three Belt miners -

Or, no. Two, and what I am beginning to fear is a mistake.

Jock had laid out the problem and the task in his customary unadorned fashion, as Roy Harris and Alexis Patel rubbed sleep from their eyes and struggled into their boots.

"Three, to go?" Alexis had said, already turning towards the rebreather rack. "I'll suit up, Captain. Do you want Roy, or will Jock -"

"Roy should stay. We will need his skills to draw us home." Harris inclined his head towards me, his deep calm soothing.

Alexis was already halfway into her suit when Anise Tang spoke, softly but clearly. "Captain."

I paused. "Cadet?"

"Captain, I believe the Guild requirements specify that cadets must be given opportunity to participate in EVA, should the ship have occasion to engage in one. During the course of its journey."

Roy sighed, while Alexis opened her mouth to speak, but Jock got there first. "Are you touched, little girl?" he barked disbelievingly. "Did you hear what I said? What the Captain said? This is no ship-shining securewalk we're talking about here. This is a job for grown-ups -"

"I heard." Tang's voice was like a starling's song laced with steel - a peculiar, unsettling effect. "We all signed danger disclaimers to board this vessel, First Officer. We will not learn enough without taking some risks. We are prepared." I stole a glance at Geryon and Desmullah, skulking behind her. They didn't look particularly prepared; they looked, in fact, as scared as we should all be, given the circumstances.

I said, "Alright, Tang. Point made." Jock began to protest, but I cut him off with my hand. "However. It is my judgement as Captain that taking all three of you would pose an unacceptable risk to the mission, and the ship." Tang's brow creasd slightly, as I went on, "One of you may take the place of Officer Patel. Only one."

So now here we are, circling in these fireflies made of the dust of stars - Jock, me, and Anise Tang. Untried, untested, and already unravelling as we move away from sanctuary in the black wilds of the Belt.

---------------------------------------------------------------------

The head mikes are scratchy. "Christina - spin left," says Jock tersely, his voice granulated by the transmission.

"Captain, Captain, I see something -"

"Where are you, Tang?" I swivel in frustration, but she's moved out of my sightlines and that's not good. Visual at all times is the rule, but she's unblooded and the rules aren't in her veins yet.

"Captain, I don't know what it is, I don't know -"

Jock interjects. "It's alright, lass," he says, his voice low, gentling her. Now that it's done and we're here with her, he knows what must be. "Tell us what you see, we'll find you."

Her breathing's ragged in the headpiece, but she says, "Tiny stars. I see ... tiny stars. Here, in front of me."

There is a pause as long as twenty heartbeats.

"Anise," I say, barely daring to breathe, "can you pull back on your tether? Can you draw back towards the ship? If you can do that, do it, and don't touch anything, alright? Just don't -"

That is when she starts screaming.

Jock's swearing in my ear and I am spinning, spinning, eyes going left right left up down right where is she where where

Then I see her, and I know it's almost certainly already too late. She's lit up like a candle on a Yule tree, her body rigid, her mouth open inside her helmet as a continuous stream of astounded agony pours out of her.

Jock is yelling at me now, Get back, get back, great gods Christina she's gonna blow any minute and I look back towards my ship, just a speck in the distance now, the dull coppery sheen of its hull a lodestone, and I say:

"Anise, Anise, I'm coming."

Jock's swearing at me in five languages now, including one I've sure has been dead since Earth fell, but I stay my course, spinning through the emptiness towards the sickly shimmering, towards the cadet, towards tiny speckled fragments of hell.

"Anise. Listen to me."

Her screams have subsided into sobs now, but they slacken, fall silent. I press my advantaage.

"You've been pierced by Casey subatoms. Do you know what they are?"

She sobs a hiccup. "Old star radiants. Rogue clusters of them out past Saturn -"

"And, apparently, in the Belt," I finish. "Although no one knew so, until now." Jock's jabbering away to Alexis back on board ship, but I mute him, moving slowly towards the shining girl.

"Yes. That's what's happened. We need to get you back to the ship and into a containment pod as soon as we can do that."

Silence. Then: "It hurts, Captain."

Her voice is fading, and I know the likelihood is she's already dead, but still I spin, concentric circles moving closer to my target with each minute.

When I get close enough to see her face through the visor, I see that her eyes, once the prettiest floss pink the geneticists of Luna could summon, are now crimson red, sightless, with blood trickling from the tear ducts like the sorrow of an ancient star.

"Anise," I say, and she raises her head towards me.

"I wanted -" she says. "My parents, they wanted me to go for a Guild marriage, be safe. But I wanted ..." Her voice is weak, distant, and hands are lax beside her.

"Come on, child," I say, as I snap her tether string to my waist belt. "Let's get you home, then." I unmute my second mike. "Jock?"

"Christina, where -"

"Jock, I'm bringing her in. Get Alexis to have the radipod ready, yes? We're coming in from the upper left."

He says nothing for a moment, then: "Christina. Any minute, she could -"

"I'll be coming in hard," I say. "Be ready, alright?"

Spinning through the dark, spinning silently, two locked-together specks of flesh, one aglow, one in shadow. People are weightless in space, but I feel the weight of her in my arms, nonetheless. She's completely quiet now; only her life signs monitor tells me she's still breathing.

"Captain!" Alexis's voice is loud, anxious, in my ear. "I've prepped the radipod, but -"

"Good. Thank you, Alexis." I can hear the downward fade in my own voice, and I look down at my hand, now starting to glow in the blackness. It was inevitable, I suppose.

"Captain, we wonder if - If she caught a full load, well -"

"We'll head straight for the field hospital. Tell Roy, yes?" And now my voice is crackling like space static even though I'm within clear visual of the ship now, in the cleanest of comm ranges.

Jock cuts in. "I'm back in the bay, Captain. Ready to catch you, when you get here."

"Thank you," I say, and then I say no more. It feels like there is no breath to speak and the pain in my chest is growing.

Thirty seconds later, I hear my own breath inside my head and I know.

The ship looms hugely in my misted sightline and I unclip Anise from my belt. "Live, then," I say, and push her towards Jock's waiting arms. They're all clustered at the dock, even the cadets, and they're shouting something towards me bur it doesn't make any sense anymore and I push away, frog-legs pressed against the hull for traction, aiming to go deep, deep, deep, before -

All the tiny stars recombine, and make an infant sun.

Saturday, February 4, 2017

The Gardens of Demos Attina (Story)

Another short story in the same universe as The Desolation of Vesta (all part of the back history of my novel in progress - The True Size of the Universe). This one is for Ren and Nadine, who said they liked the first one and asked for more :-)

The Seven Climate Gardens of Demos Attina are the first, and for me, the most beautiful, of the seven wonders of the Star-Free worlds.

Taking up fully a quarter of the City dome in the capital city of Demos, Queen of Moons, the gardens represent an achievement so exquisite, so complete, so utterly nostalgic, as to render them almost plastique in their perfection. One to represent each major climate from poor dear Mother Earth, before the Vandals ensured that our natal home has only one climate, and that a barren one.

I have loved them all in equal measure in my time. The Garden of Hot Desert, with its oases and bright, startlingly soft sands; The Polar Garden, for which entrants must sign a disclaimer and hire expedition gear for the gruelling slog over ice sheets to the summits.

The Rainforest Garden, smelling like life and like vegetable rot, burgeoning with colour and the screech of monkeys high in the canopy. The Plains Garden, a wheat-light savannah stretching as far as the eye can see (or be tricked into thinking it sees, in any case).

The Mediterranean Garden, apex of delights, with its falls of grape vines and its cool, misting morning rains. The Cold Country Garden ("merry olde England", my grandfather used to call it), the most built-upon of all the gardens, with its stables full of riding mammals regenerated from DNA stocks, its tea rooms, its lightly forested bridle paths.

I loved then all, yes; but it was to the Subtropical Garden, smelling like jasmine and river water, wet with monsoon artfully generated from the intricacies of the algorithms operating the subdomic controls, that I brought my wife to kill her.

--------------------------------------------

The LEO looks at me thoughtfully over the table.

"You don't wish to access your right to counsel?"

I shake my head; no, no. As I have done many times already in this small, cold room.

"You understand we'll be charging you with murder, then."

I say, "I do." My hands are folded in front of me, and they are still. The LEO frowns. I think she is more accustomed to agitation, unrestfulness, fury, in her arrestees. But then, most people protest their innocence, I believe. I have no such protestation to make.

She pushes a mug of coffee towards me, not ungraciously. "Your wife was a senior Master with the Guild. Rosinta Swann."

"Yes," I say, and I think my voice is affectless. "She was a person of importance, here in Attina, far beyond. That is true."

The LEO scratches at the ear where her mike is tucked in tightly; it must be ill-fitted to chafe so. Or perhaps she just doesn't like the orders she's getting from outside.

"Miz Gynt ... or can I can you Nadine?"

"If you prefer," I say. It doesn't matter. Not now.

"Nadine. Well. The Guild wants to know why you killed your wife. It's important to them to know."

I shrug indifferently, and speak aloud my earlier thoughts. "It doesn't matter. Not now."

The LEO's gaze is steady, so it takes me a minute to realise that her hands are moving under the table, out of sight of the cameras. I flick my eye, ever so slightly, and what I read from her fingers stiffens my spine like a bolt of electricity.

She says: "Perhaps you would feel more like talking if we took you back to the scene of your crime." She invests her voice with all the venom and promise that storybook old-world cops could, but I am still responding to her long brown hands and I merely say, "As you like, of course."

---------------------------------------------------------------

Three LEOs escort me back to the gates of Climate Garden 6. The sign announces: Subtropical Monsoon (Beware Biting Insectoids) - Earth Analogue South-East Asia, Pacific Islands, Northern Australia.

The gates, normally left ajar, have been sealed with a laser LEO tag marking an active crime scene. There are clumps of people gathered, muttering, pointing, but no-one comes near as we alight from the hovercar and break the seal to enter. I think I hear one woman say, "But that's her wife, surely - the artist, the immigrant from Copernica Luna?" but we have moved inside the gates before I can hear her companion's reply.

Inside, the micro-climate takes over quickly. The three LEOS' stiff white shirts are sweat-softened and drooping within minutes, and my interrogator's round face is reddening alarmingly. She grunts a command and one of the group drops back to the gate, no doubt to discourage curious onlookers.

"Nadine. We found the body on the banks of the river; is that where you killed her?" My interrogator's face is serious, but her hands are twitching, just slightly but I can see them.

"What is your name?" I say. It suddenly seems like something I should know.

She pauses. "Ah. My name is Adjunct Yellowlees. Attina Serious Crimes Division." She nods her head towards the young boy in uniform beside us. "This is Recruit Yui."

I say nothing with my mouth, but my fingers move, as quietly as carp in the water. Her eyes dilate the merest fraction, but she says, "Yui. Can you scan the perimter, please?" The boy lopes off, his stunner held in a loose-gripped brown paw.

Yellowlees looks at me and says, "Hala. You can call me Hala."

Welcome always, sister, my fingers say.

I cannot see you freed. I cannot do much at all, her fingers reply, her frustration and grief adding sharpness to the movements.

No matter, my friend. I will free myself, when the time comes. You must only carry the tale, and let it be heard.

"Shall we proceed to the site, Nadine?" says Hala Yellowlees, her voice formal. I incline my head slightly and allow her to lead me to the place under the weeping tree where I laid my wife's body down when I had stolen her last breath into my mouth.

"We found Master Swann ... here." She touches the marked outline with her toe. "She had been poisoned, apparently with food or drink that you served to her on a picnic -"

"It was in the wine," I say absently. "A soporific. There was no pain." I pause. "We were on a boat. On the river. When she drank the wine."

Dutifully, Hala activates her 'corder and notes this detail. "Did you move her from the boat before after her death?"

I consider this. "Before," I say. What's the point in lying now, or to this woman? Even if there is one secret I will keep tucked away in my heart.

"So she was sleeping when you laid her here?"

"Yes. Sleeping, but sinking. The narcotic was well underway by then."

Hala opens her left hand, the one she's been clenching tightly beside her, and a scatterbomb frolics up into the air, fizzing and popping as they are wont to do. That buys as much as five full minutes free of surveillance, here in the gardens where the sensors are widely spread and difficult for the repair-bots to access. Maybe more in Garden Six, where the ambient humidity plays merry hell with the wiring at the best of times.

"We can speak freely," she says, and takes my forearm. "You are Resistance, yes?"

"Of course," I say. "Of course, I am, as all people of conscience must be." I reach up to touch her smooth brown cheek. "You also, little sister. Why, for you?"

She gives me a sad smile. "I was born on Luna, too, but not in Copernica like you. I was born in Bailly." I take an involuntary breath in. "When you have seen your home, your family, so devastated by the Guild ... oh, it was good economics, they said, but not for us. Not for us."

I nod. "Trade does not count the human heart in its balance sheets," I say. "Nor consider that all life is life, not tradeable commodities."

"What brought you to it?" she asks. "I know we haven't the time, but -"

I look out, towards the river, its waters lapping the roots of the weeping tree. "I have seen too much," I say, finally. How can I explain thirty years in a moment? The words are inadequate, but they will have to do.

"Why now? Why kill her now?" She needs to know this, the Movement needs to know it; it matters, so the fact that it hurts is immaterial.

I say, "Because she was leading a project to drain Ceres dome of its atmo and repossess it. Because a new, massive deposit of mixed uranium and radium had turned up right under the dome, and it's worth more than the last twenty years' worth of Belt scratchings combined. Because the Council of Ceres has resisted all attempts to evict them and their citizenry and has declared themselves outside of the Guild. So she was going to asphyxiate them. All of them. Then they were going to claim it was an accidental system failure, very unfortunate, so sad." I pause. "They would've built a beautiful monument to the lost souls of Ceres, on the edge of the mine pit."

Hala's face is slack with shock. I feel sad as I see her horror. Contemplating the mass murder of 2 million people isn't an easy thing, after all. How can I tell her that, in my thirty years of marriage, this is not the worst thing I have witnessed, nor heard my wife tell of, encased in the armour of her own conviction that wealth is the same thing as worth? Not the worst, but simply the final straw.

"Will they still do it? Now?" she says, almost whispering, as if to belay the disgust churning below.

I shrug. "My wife was instrumental to the Project, so not quickly. If you get the word out, not at all. It only works if they have plausible deniability, you see? The Guild is not built of fools."

She nods, brisk now. She knows what she needs to do. It's a boon, having her here; I need not, now, go through the laborious and chancy process of getting a message out from prison through the Resistance networks. This is much cleaner and more sure.

I say, "Hala." Her eyes are sad as she asks me, fingerswift now: Are you sure?

Oh yes, little sister. Let me free myself, now. Carry the word. Let the people see, and be free.

She presses my arm tightly as she hands me her weapon. "You're a hero," she says, her voice shaking. "A true hero, to have endured thirty years ... and now, to have saved a whole City. Blessed be, mother."

"Blessed be, daughter," I murmur, and watch her walk away, her back stiff with purpose.

Now I stand on the banks of this perfume river, my ocean-green eyes clouded over with the past, and inhale the good scent of the blossoms falling like snow into the water. I think how wrong Hala was, so young, so idealistic. I think how I bent to kiss my wife into her final sleep, drawing her breath into my lungs, filling myself with her.

I think how I am no hero at all.

Oh, Rosinta. I did not stay with you to do the work of Resistance. I stayed because I loved you too much to go.

I can see a heron rising from the shallows. I follow it with my eyes as it spirals up, up, up, and I raise the weapon.

The sky lights up.

The Seven Climate Gardens of Demos Attina are the first, and for me, the most beautiful, of the seven wonders of the Star-Free worlds.

Taking up fully a quarter of the City dome in the capital city of Demos, Queen of Moons, the gardens represent an achievement so exquisite, so complete, so utterly nostalgic, as to render them almost plastique in their perfection. One to represent each major climate from poor dear Mother Earth, before the Vandals ensured that our natal home has only one climate, and that a barren one.

I have loved them all in equal measure in my time. The Garden of Hot Desert, with its oases and bright, startlingly soft sands; The Polar Garden, for which entrants must sign a disclaimer and hire expedition gear for the gruelling slog over ice sheets to the summits.

The Rainforest Garden, smelling like life and like vegetable rot, burgeoning with colour and the screech of monkeys high in the canopy. The Plains Garden, a wheat-light savannah stretching as far as the eye can see (or be tricked into thinking it sees, in any case).

The Mediterranean Garden, apex of delights, with its falls of grape vines and its cool, misting morning rains. The Cold Country Garden ("merry olde England", my grandfather used to call it), the most built-upon of all the gardens, with its stables full of riding mammals regenerated from DNA stocks, its tea rooms, its lightly forested bridle paths.

I loved then all, yes; but it was to the Subtropical Garden, smelling like jasmine and river water, wet with monsoon artfully generated from the intricacies of the algorithms operating the subdomic controls, that I brought my wife to kill her.

--------------------------------------------

The LEO looks at me thoughtfully over the table.

"You don't wish to access your right to counsel?"

I shake my head; no, no. As I have done many times already in this small, cold room.

"You understand we'll be charging you with murder, then."

I say, "I do." My hands are folded in front of me, and they are still. The LEO frowns. I think she is more accustomed to agitation, unrestfulness, fury, in her arrestees. But then, most people protest their innocence, I believe. I have no such protestation to make.

She pushes a mug of coffee towards me, not ungraciously. "Your wife was a senior Master with the Guild. Rosinta Swann."

"Yes," I say, and I think my voice is affectless. "She was a person of importance, here in Attina, far beyond. That is true."

The LEO scratches at the ear where her mike is tucked in tightly; it must be ill-fitted to chafe so. Or perhaps she just doesn't like the orders she's getting from outside.

"Miz Gynt ... or can I can you Nadine?"

"If you prefer," I say. It doesn't matter. Not now.

"Nadine. Well. The Guild wants to know why you killed your wife. It's important to them to know."

I shrug indifferently, and speak aloud my earlier thoughts. "It doesn't matter. Not now."

The LEO's gaze is steady, so it takes me a minute to realise that her hands are moving under the table, out of sight of the cameras. I flick my eye, ever so slightly, and what I read from her fingers stiffens my spine like a bolt of electricity.

She says: "Perhaps you would feel more like talking if we took you back to the scene of your crime." She invests her voice with all the venom and promise that storybook old-world cops could, but I am still responding to her long brown hands and I merely say, "As you like, of course."

---------------------------------------------------------------

Three LEOs escort me back to the gates of Climate Garden 6. The sign announces: Subtropical Monsoon (Beware Biting Insectoids) - Earth Analogue South-East Asia, Pacific Islands, Northern Australia.

The gates, normally left ajar, have been sealed with a laser LEO tag marking an active crime scene. There are clumps of people gathered, muttering, pointing, but no-one comes near as we alight from the hovercar and break the seal to enter. I think I hear one woman say, "But that's her wife, surely - the artist, the immigrant from Copernica Luna?" but we have moved inside the gates before I can hear her companion's reply.

Inside, the micro-climate takes over quickly. The three LEOS' stiff white shirts are sweat-softened and drooping within minutes, and my interrogator's round face is reddening alarmingly. She grunts a command and one of the group drops back to the gate, no doubt to discourage curious onlookers.

"Nadine. We found the body on the banks of the river; is that where you killed her?" My interrogator's face is serious, but her hands are twitching, just slightly but I can see them.

"What is your name?" I say. It suddenly seems like something I should know.

She pauses. "Ah. My name is Adjunct Yellowlees. Attina Serious Crimes Division." She nods her head towards the young boy in uniform beside us. "This is Recruit Yui."

I say nothing with my mouth, but my fingers move, as quietly as carp in the water. Her eyes dilate the merest fraction, but she says, "Yui. Can you scan the perimter, please?" The boy lopes off, his stunner held in a loose-gripped brown paw.

Yellowlees looks at me and says, "Hala. You can call me Hala."

Welcome always, sister, my fingers say.

I cannot see you freed. I cannot do much at all, her fingers reply, her frustration and grief adding sharpness to the movements.

No matter, my friend. I will free myself, when the time comes. You must only carry the tale, and let it be heard.

"Shall we proceed to the site, Nadine?" says Hala Yellowlees, her voice formal. I incline my head slightly and allow her to lead me to the place under the weeping tree where I laid my wife's body down when I had stolen her last breath into my mouth.

"We found Master Swann ... here." She touches the marked outline with her toe. "She had been poisoned, apparently with food or drink that you served to her on a picnic -"

"It was in the wine," I say absently. "A soporific. There was no pain." I pause. "We were on a boat. On the river. When she drank the wine."

Dutifully, Hala activates her 'corder and notes this detail. "Did you move her from the boat before after her death?"

I consider this. "Before," I say. What's the point in lying now, or to this woman? Even if there is one secret I will keep tucked away in my heart.

"So she was sleeping when you laid her here?"

"Yes. Sleeping, but sinking. The narcotic was well underway by then."

Hala opens her left hand, the one she's been clenching tightly beside her, and a scatterbomb frolics up into the air, fizzing and popping as they are wont to do. That buys as much as five full minutes free of surveillance, here in the gardens where the sensors are widely spread and difficult for the repair-bots to access. Maybe more in Garden Six, where the ambient humidity plays merry hell with the wiring at the best of times.

"We can speak freely," she says, and takes my forearm. "You are Resistance, yes?"

"Of course," I say. "Of course, I am, as all people of conscience must be." I reach up to touch her smooth brown cheek. "You also, little sister. Why, for you?"

She gives me a sad smile. "I was born on Luna, too, but not in Copernica like you. I was born in Bailly." I take an involuntary breath in. "When you have seen your home, your family, so devastated by the Guild ... oh, it was good economics, they said, but not for us. Not for us."

I nod. "Trade does not count the human heart in its balance sheets," I say. "Nor consider that all life is life, not tradeable commodities."

"What brought you to it?" she asks. "I know we haven't the time, but -"

I look out, towards the river, its waters lapping the roots of the weeping tree. "I have seen too much," I say, finally. How can I explain thirty years in a moment? The words are inadequate, but they will have to do.

"Why now? Why kill her now?" She needs to know this, the Movement needs to know it; it matters, so the fact that it hurts is immaterial.

I say, "Because she was leading a project to drain Ceres dome of its atmo and repossess it. Because a new, massive deposit of mixed uranium and radium had turned up right under the dome, and it's worth more than the last twenty years' worth of Belt scratchings combined. Because the Council of Ceres has resisted all attempts to evict them and their citizenry and has declared themselves outside of the Guild. So she was going to asphyxiate them. All of them. Then they were going to claim it was an accidental system failure, very unfortunate, so sad." I pause. "They would've built a beautiful monument to the lost souls of Ceres, on the edge of the mine pit."

Hala's face is slack with shock. I feel sad as I see her horror. Contemplating the mass murder of 2 million people isn't an easy thing, after all. How can I tell her that, in my thirty years of marriage, this is not the worst thing I have witnessed, nor heard my wife tell of, encased in the armour of her own conviction that wealth is the same thing as worth? Not the worst, but simply the final straw.

"Will they still do it? Now?" she says, almost whispering, as if to belay the disgust churning below.

I shrug. "My wife was instrumental to the Project, so not quickly. If you get the word out, not at all. It only works if they have plausible deniability, you see? The Guild is not built of fools."

She nods, brisk now. She knows what she needs to do. It's a boon, having her here; I need not, now, go through the laborious and chancy process of getting a message out from prison through the Resistance networks. This is much cleaner and more sure.

I say, "Hala." Her eyes are sad as she asks me, fingerswift now: Are you sure?

Oh yes, little sister. Let me free myself, now. Carry the word. Let the people see, and be free.

She presses my arm tightly as she hands me her weapon. "You're a hero," she says, her voice shaking. "A true hero, to have endured thirty years ... and now, to have saved a whole City. Blessed be, mother."

"Blessed be, daughter," I murmur, and watch her walk away, her back stiff with purpose.

Now I stand on the banks of this perfume river, my ocean-green eyes clouded over with the past, and inhale the good scent of the blossoms falling like snow into the water. I think how wrong Hala was, so young, so idealistic. I think how I bent to kiss my wife into her final sleep, drawing her breath into my lungs, filling myself with her.

I think how I am no hero at all.

Oh, Rosinta. I did not stay with you to do the work of Resistance. I stayed because I loved you too much to go.

I can see a heron rising from the shallows. I follow it with my eyes as it spirals up, up, up, and I raise the weapon.

The sky lights up.

Friday, February 3, 2017

A study in frustration

Today I decided that, since I had a bit of unallocated time, I should start the passport application process for Japan in 2018.

First step: Identify if anyone still has a valid passport. All the passports are in the Legal Documents file, yay! Looks like my husband's is valid til 2020, so no passport application needed for him. One down, four to go.

Second step: Find birth certificates for those needing passports.

You'd THINK that would be easy, right, given that I HAVE A FILE LABELLED LEGAL DOCUMENTS? That file contained a photocopy (not acceptable for this purpose) of my eldest's certificate, plus a very battered certificate for my secondborn. Bupkiss for the youngest and I.

Then commenced Project Tear the House Apart Because I Know I Goddamn Had These!!! I pulled open my huge storage cupboard that is filled with literally mountains of paper. I ripped through my junk piles near the door, in my room, in my desk.

I chucked out a mahoosive heap of junk so there's that, and for my efforts, I found:

- School photo sets I thought were lost years ago

- The missing year's Santa photo

- Everyone's school reports

- My pregnancy diary from my pregnancy with my secondborn and...

- Three birth certificates!

Yay, you might think - but actually not really. The three I found were mine (so that's one tick) and ... two MORE clean versions of secondborn's. So we can verify the shit out of HER birth, but not the eldest's or the youngest's.

I know perfectly well what happened to them - I had to present them as proof of birth when each started at school (youngest in 2014, eldest for starting high school last year) and I took them out of their safe place in the file and then ... did not return them. I thought this would mean they were skulking about somewhere in school paperwork - that's where the second copy of middle kid's was - but alas, no.

I am now sitting in a veritable sea of paper, scowling at the screen on Births, Deaths & Marriages' online page trying to figure out if there is any way I can get certificates for eldest and youngest without a shit-boring trek into the city and sitting around waiting. As I need to verify my ID to them, I don't think there is. What a nuisance :-( :-(

And to think this could all have been avoided if I wasn't such a slob.

First step: Identify if anyone still has a valid passport. All the passports are in the Legal Documents file, yay! Looks like my husband's is valid til 2020, so no passport application needed for him. One down, four to go.

Second step: Find birth certificates for those needing passports.

You'd THINK that would be easy, right, given that I HAVE A FILE LABELLED LEGAL DOCUMENTS? That file contained a photocopy (not acceptable for this purpose) of my eldest's certificate, plus a very battered certificate for my secondborn. Bupkiss for the youngest and I.

Then commenced Project Tear the House Apart Because I Know I Goddamn Had These!!! I pulled open my huge storage cupboard that is filled with literally mountains of paper. I ripped through my junk piles near the door, in my room, in my desk.

I chucked out a mahoosive heap of junk so there's that, and for my efforts, I found:

- School photo sets I thought were lost years ago

- The missing year's Santa photo

- Everyone's school reports

- My pregnancy diary from my pregnancy with my secondborn and...

- Three birth certificates!

Yay, you might think - but actually not really. The three I found were mine (so that's one tick) and ... two MORE clean versions of secondborn's. So we can verify the shit out of HER birth, but not the eldest's or the youngest's.

I know perfectly well what happened to them - I had to present them as proof of birth when each started at school (youngest in 2014, eldest for starting high school last year) and I took them out of their safe place in the file and then ... did not return them. I thought this would mean they were skulking about somewhere in school paperwork - that's where the second copy of middle kid's was - but alas, no.

I am now sitting in a veritable sea of paper, scowling at the screen on Births, Deaths & Marriages' online page trying to figure out if there is any way I can get certificates for eldest and youngest without a shit-boring trek into the city and sitting around waiting. As I need to verify my ID to them, I don't think there is. What a nuisance :-( :-(

And to think this could all have been avoided if I wasn't such a slob.

Thursday, February 2, 2017

Home

Last night - or, rather, in the early hours of the morning, once I fell back asleep after my customary 4am waking for asthma medication and bladder evacuation - I dreamed extremely vividly of my parents' house, the house I grew up in.

This is not the first time I have had such a dream, in the 18 months since they sold the property and moved first to a temporary flat and later their pleasant new unit in a complex of eight. In fact, although the details vary, you could say it's become a recurring dream, or at least a recurring theme, in my almost-lucid, vivid, emotionally fraught early morning REM cycles.

In these dreams, the story usually goes something like this:

- For some reason, we still have keys to my parents' old house and the keys still work.

- The property is derelict, left entirely abandoned by its now owners. (This part is sort of true - the house has indeed sat vacant for a year and a half, garden overgrown, my Dad's beloved roses choking to death, as the investor who bought it negotiates their next option).

- For some reason that is never clear, we (that is, my husband, my daughters, my brother, my sister in law and me) decide that we need or want to go and stay in the house.

- We let ourselves in, set up camp in the various rooms, and live like squatters, parking our cars out of sight in what used to be the old vet surgery carpark at the back. Nothing works in the house so we live without cooking, light or washing / toilet facilities, but for some reason, this doesn't seem important in the dream.

- We hear the sounds of people coming to the door and we panic, try to get out. Sometimes this involves us running out the back door, sometimes, because it is, after all, a dream world, we all fly out of the back windows and into the cloudy sky.

- One person gets left behind (not always the same person) and I go back for them.

- When I go back, the house is full of angry strangers who are trying to hurt us but don't succeed. I end up yelling something like "This is MY HOUSE!"or "It doesn't belong to YOU!"at them.

It's interesting, and probably says something profoundly weird about my psyche. I've never really gone in for dream analysis, but I confess I'd be curious to know what an analyst made of this. '

In my conscious mind, I wasn't excessively attached to my parents' home. Yes, I grew up there - we moved in when I was 2, so I don't remember living anywhere else - but I left, and was keen to leave, at 21, moving into a share house first and later heading to other side of the city when I married. Our family home now, where I live with my husband and three girls, has been my home for almost 14 years, and most of the key milestones of my life have happened here. (And yes, I do feel attachment to my current home, which was underlined strongly when we considered moving a while back - I had both a practical and psychological reluctance to do so).

I didn't even particularly like the house I grew up in as a house. It was a stolid, not very pretty, red brick bungalow on a major highway - it was always dusty and polluted air outside, and noisy all night, and I vowed I'd never again live on a main road (I never have!) My Dad grew a lovely garden and I did like that, but the house itself was just ... the house, the place we lived, the place we ate and talked and washed and slept and studied and read and laughed and cried.

Oh yes. And the place my brother lived the entire 8 years of his short life. All the walls were embedded with him, and the memories of him. It was the place I brought my own babies to, when I needed my Mum and her loving touch. It was the place that always looked the same and smelled like roast dinners and tea and clean laundry. It was the place with cool spots and warm spots and the story of my coming of age written in the bookshelves and the carpets, the curtains and the big ceramic bathtub.

Maybe I'm not really grieving the house at all.

This is not the first time I have had such a dream, in the 18 months since they sold the property and moved first to a temporary flat and later their pleasant new unit in a complex of eight. In fact, although the details vary, you could say it's become a recurring dream, or at least a recurring theme, in my almost-lucid, vivid, emotionally fraught early morning REM cycles.

In these dreams, the story usually goes something like this:

- For some reason, we still have keys to my parents' old house and the keys still work.

- The property is derelict, left entirely abandoned by its now owners. (This part is sort of true - the house has indeed sat vacant for a year and a half, garden overgrown, my Dad's beloved roses choking to death, as the investor who bought it negotiates their next option).

- For some reason that is never clear, we (that is, my husband, my daughters, my brother, my sister in law and me) decide that we need or want to go and stay in the house.

- We let ourselves in, set up camp in the various rooms, and live like squatters, parking our cars out of sight in what used to be the old vet surgery carpark at the back. Nothing works in the house so we live without cooking, light or washing / toilet facilities, but for some reason, this doesn't seem important in the dream.

- We hear the sounds of people coming to the door and we panic, try to get out. Sometimes this involves us running out the back door, sometimes, because it is, after all, a dream world, we all fly out of the back windows and into the cloudy sky.

- One person gets left behind (not always the same person) and I go back for them.

- When I go back, the house is full of angry strangers who are trying to hurt us but don't succeed. I end up yelling something like "This is MY HOUSE!"or "It doesn't belong to YOU!"at them.

It's interesting, and probably says something profoundly weird about my psyche. I've never really gone in for dream analysis, but I confess I'd be curious to know what an analyst made of this. '

In my conscious mind, I wasn't excessively attached to my parents' home. Yes, I grew up there - we moved in when I was 2, so I don't remember living anywhere else - but I left, and was keen to leave, at 21, moving into a share house first and later heading to other side of the city when I married. Our family home now, where I live with my husband and three girls, has been my home for almost 14 years, and most of the key milestones of my life have happened here. (And yes, I do feel attachment to my current home, which was underlined strongly when we considered moving a while back - I had both a practical and psychological reluctance to do so).

I didn't even particularly like the house I grew up in as a house. It was a stolid, not very pretty, red brick bungalow on a major highway - it was always dusty and polluted air outside, and noisy all night, and I vowed I'd never again live on a main road (I never have!) My Dad grew a lovely garden and I did like that, but the house itself was just ... the house, the place we lived, the place we ate and talked and washed and slept and studied and read and laughed and cried.

Oh yes. And the place my brother lived the entire 8 years of his short life. All the walls were embedded with him, and the memories of him. It was the place I brought my own babies to, when I needed my Mum and her loving touch. It was the place that always looked the same and smelled like roast dinners and tea and clean laundry. It was the place with cool spots and warm spots and the story of my coming of age written in the bookshelves and the carpets, the curtains and the big ceramic bathtub.

Maybe I'm not really grieving the house at all.

Wednesday, February 1, 2017

The Desolation of Vesta (Story)

Month of Poetry is over - alas! it's always one of my favourite things in the year - but as part of my creative goal, I also signed up to do Write Every Day for a Year Challenge. Without my daily poem to fill the requirement, today I've tried a little short-short that fits within the general universe of one of my novel WIPs, The True Size of the Universe, but is not directly related to the novel's story and doesn't involve any of the novel's characters. It's science fiction insofar as it takes place in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, and about 300 years in the future, but it's not a science story - it's a human one (I hope).

The ships stopped coming when I was nine, or maybe ten.

Before that, things were busy all the time, the port humming with life, people swarming everywhere in the City dome. Belt-miners, mostly; hard-edged people, some watchful-quiet, some over-loud, all with their hands firm on their pockets. Mining the belt paid exceedingly well, and those who did it kept their money close and their secrets closer. It was a knacky sort of business - sensors and probes could only tell you so much, and there was an element of intuition to it that couldn't be replaced with robotics. Miners held their veins as close as any grubstaker in the goldfields, back on Earth, before the guts were all ripped out of the rock.

They were all guns for hire, of course; the Guild of Moons controlled all the mining in the Belt, in the days when there were still things of value to be ground from the planetismals that circled in the air like fireflies in the climate gardens of Demos Attina. A good miner, though, could make a lifetime's comfort from ten productive years in the Belt, with the danger money and the finder's fees the Guild corporates lavished on them.

"Why do they always have so much?" I'd asked my father, resentful, as I sipped at the bland protein slush in front of me, watching as a tableful of miners carved up a Phobaen octopoid beside us.

"Their work ... it's risky," my father had said, his eyes creasing against the sudden flare of the flambe as the bananas foster arrived in their chafing dish. The party of miners set up a ragged cheer at the sudden caramel sweetness of the air.

"But I don't understand why -"

"Hush, Ren." My father's voice was distracted, his eyes drawn outwards to the view of the port from the window.

"They wouldn't even be able to land here without us," I muttered, but mostly to myself. Even though it was true enough - Port-adapted Vestans all took a hand in piloting the chunky round-bellied mining rigs into the little jagged docking array, even the kids, once we were old enough for some responsibility.

My mother had explained why, once - the piloting mind-mutation was specialised, and difficult to replicate artificially, so the easiest and best way to keep a Belt port staffed was to create new pilots through in-breeding the traits to strengthen them - the old-fashioned way.

Of course, that also meant a lifetime in the Belt, for those of us born to it. You could move around among the stations - my cousin Pilani was Assistant Portmaster at Ceres Base, a great honour, as my father never ceased reminding us - but port-adapted pilots were not permitted to settle outside the Belt, by Guild edict.

"Not the fairest thing, perhaps," she'd said; then, catching my father's eye: "But we have food enough, and good shelter, schooling, books, good medical care ... and the function is vital."

"We are needed where we are," my father had said. "And one day I'll take you to Mars Prime, you'll see. We can walk the Twenty-Seven Levels together, top to toe."

That night, I'd asked my mother: "Is Mars Prime beautiful? As beautiful as they say?"

She sighed and tucked my hair behind my ear. "I don't know, Ren," she'd said.

"But you must have been," I insisted, sitting up in bed to gesticulate grandly out the plas-glass window. "The system, you and Daddy must have ... He says we'll go to see everything ..."

She shook her head, her eyes clouded. "I've never been further than Hygiea," she said. "Your father's been to Ceres once, to visit with Pilani. That was before you were born. Port-Adapts ... we don't leave the Belt. Not really. It's hard to get the permits, hard to go -"

"But you want to," I'd said, rubbing the back of her hand onto my cheek. "You want to go. Don't you, Mummy? We could go together?"

I remember that she lay down with me a long time, that night.

__________________________________________________

My father said, "They're coming in too hot."

I stared at him, at the flat shock in his voice, and swung around to the picture window. Dimly, beside me, I heard the shouts of the miners as they surged towards the glass, faces shelled open in alarm. Somewhere, a beaker smashed on the hard rock floor.

And the ship hit the deck hard, too hard, much too hard, and exploded.

Even from where we were, tucked up behind triple-sheeted plas-glass in the City dome, I thought I could feel the heat of it, radiating forward as the entire dock spurted into green-orange flames. The cursing of the miners, watching their ships and loads burn, mingled with a sickness that grew and grew until I said, loud, too loud:

"Who was piloting the ships?"